Decoding the Past: Ancient DNA and Direct to Consumer Technologies

Discoveries in Maryland with ancient DNA

I’m always excited about the opportunity to blend science and storytelling. When Science reached out about a new paper at the intersection of ancient DNA research and direct-to-consumer genetic technologies, I knew it would be a fun one!

Let’s walk through the story of buried African ancestry at Catoctin Furnace in Maryland.

Decoding the Past

Furnaces were crucial to the development of the colonies and the United States, and the impact of furnaces and forges can be clearly seen from the Revolutionary War and even earlier. The Catoctin Iron Furnace in Maryland sits in Cunningham Falls State Park, not that far from where I used to work. The proximity to my route between DC and Gettysburg only made me even more interested in this story.

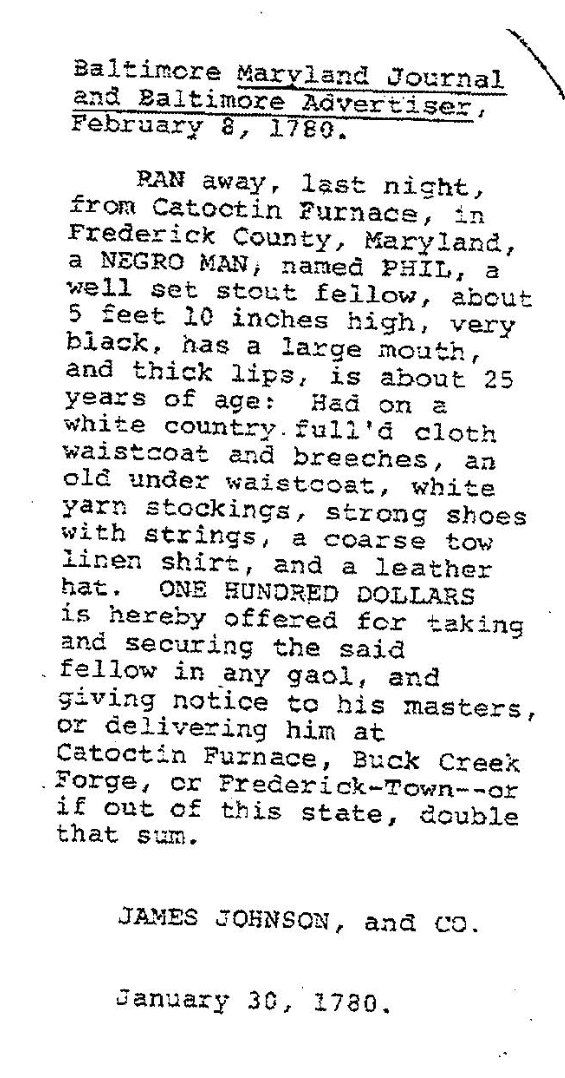

The Catoctin Furnace used the labor of enslaved people. As I prepared for the story, I reviewed freedom seeker ads about enslaved people running away, seeking their freedom from Catoctin Furnace. Over time the workers became a mix of free, formerly enslaved, and enslaved African Americans, until eventually, the furnace moved to white laborers. The enslaved and free African Americans were buried in a cemetery near the furnace, but when a highway was built ~1980, part of the cemetery was excavated.

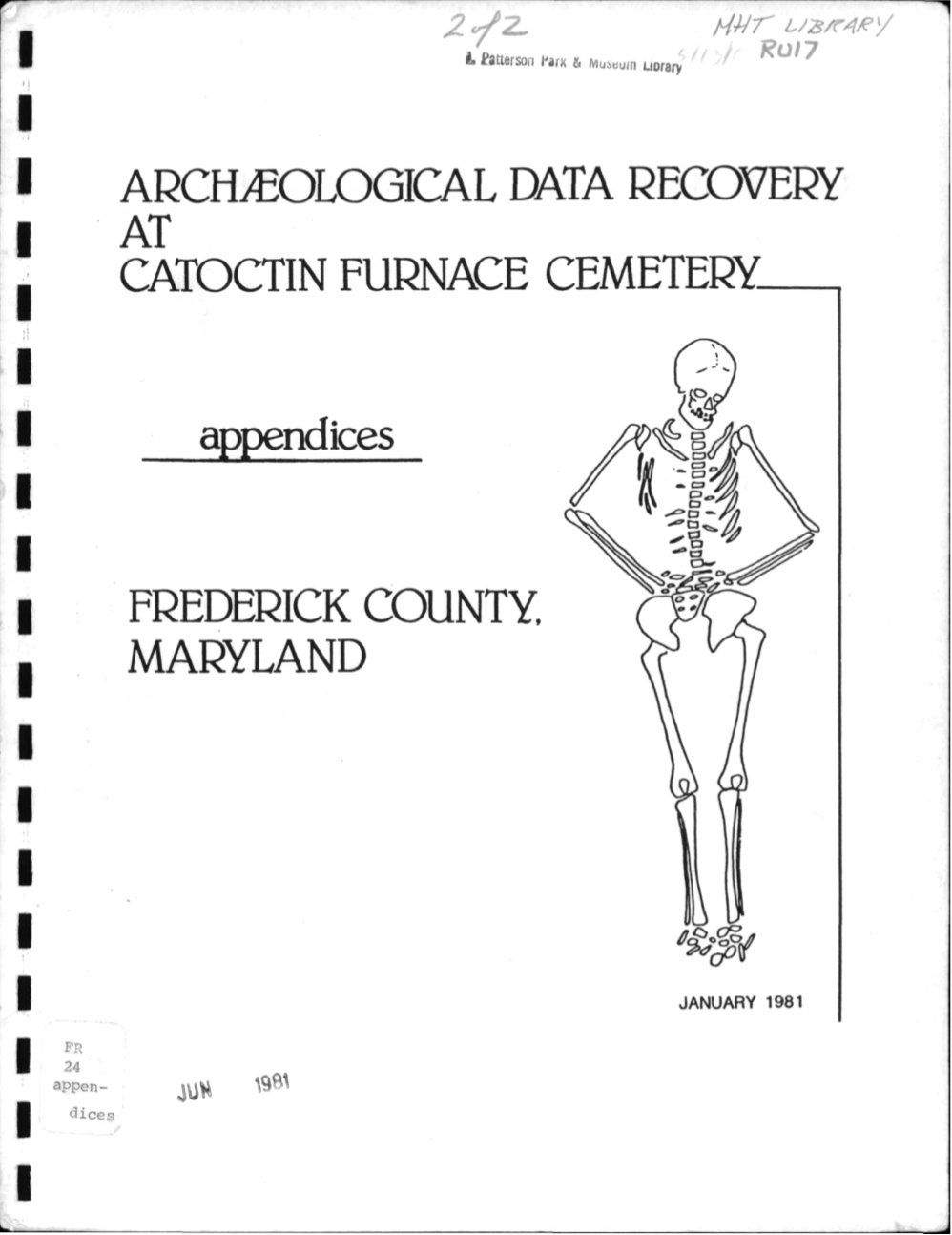

There was a report produced that detailed the history of both free and enslaved black people at Catoctin Furnace and nearby Frederick, the physical anthropological findings of the excavation, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of National History’s possession of the recovered skeletons, and more.

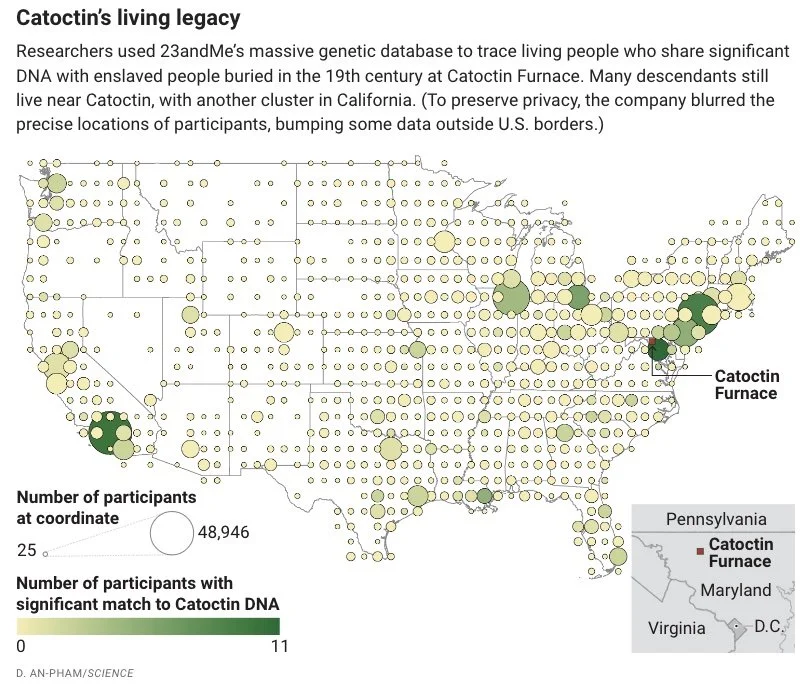

While it was clear that the African Americans who worked at the furnace contributed to the Industrial Revolution with their labor, their stories remained lost. The Catoctin Furnace Historical Society was unable to locate descendants of the enslaved ironworkers despite multiple efforts over the years.

The Report after the Excavation. Click to read full Report.

Unraveling Complexities

There’s quite a bit to unpack when it comes to the bringing these types of stories, the buried histories of the enslaved, to the light. There’s the technological advances and then there’s the ethical and social questions that stem from this type of work. As I stated on the podcast, “Normally, if you were looking at remains or wanting to do any kind of genetic study of remains, you would ask the family if you could have permission, but the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, hasn't been able to make much progress with identifying descendants.”

The Legacy of the catoctin furnace descendants

Without knowledge of the descendants, you can’t really ask for permission to complete genetic testing on the remains of these individuals. On the other hand, this is exactly the problem they're trying to solve, and completing this genetic testing may bring them closer to identifying the community of relatives. In my opinion, that’s what makes this type of work both important and a little tricky.

I’ve talked about direct to consumer genetic testing before. I think it’s a powerful tool but a dangerous thing in the hands of the uninformed. I’ve talked about folks completing kits like 23andme, then uploading their genetic information to unprotected databases to solve crimes and find other relatives. In a way, your DNA isn’t just yours, and even if it was - that’s a wild way to throw it around. You can listen to more of my thoughts about that on an earlier episode of Dope Labs, Lab 009: How NOT to Get Away with Murder.

I think the discoveries the researchers were able to make about the descendants and other close relatives were absolutely amazing. I encourage you to listen 🎧 to the story to learn more. While some of the credit goes to advanced DNA technologies, this team couldn’t have made this type of connection without a robust database, and that’s what 23andme provided. On one hand we need more participation in databases like these for this very reason. On the other hand, what happens when we’re no longer in control of who has access to the data?

Additional Reading & Related Media

Original Research Article - The genetic legacy of African Americans from Catoctin Furnace

Tracing the genetic history of African Americans using ancient DNA, and ethical questions at a famously weird medical museum - Science Podcast

Community-initated genomics by Fatimah Jackson (Howard University)

Enslaved African Americans in Maryland Linked to 42,000 Living Relatives by Carl Zimmer in NYTimes

Cemetery DNA links enslaved people at hellish forge to living descendants. Should they be contacted?

African Americans in the Catoctin Mountains - National Park Service

Knowledge and Attitudes about Privacy and Secondary Data Use among African-Americans Using Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing (24 individuals interviewed)

“Discussion/Conclusion: This study found that African-American consumers of DTC GT had a positive outlook about genetic testing and were open to research and some nonresearch uses, provided that they were able to give informed consent. Participants in this study had little knowledge of company practices regarding secondary uses. Compared to an earlier cohort of European American participants, African-American participants expressed more concerns about medical and law enforcement communities’ use of data and more reference to community engagement.”

Racial minority group interest in direct-to-consumer genetic testing: findings from the PGen study (Small sample size of non-white racial minorities)

Catoctin Furnace African American Cemetery Interpretive Trail Audio Tour - YouTube

How long can ancient DNA survive - Science Podcast